Because it’s December and Christmas decorations are everywhere, I wrote last night about the meanings and etymology of the word ‘bauble’ on WordyNerdBird. I wondered then if it were a word used by Shakespeare. To my delight, it was indeed!

Interestingly, Shakespeare references one of the continued senses and the obsolete sense of the word, and creates double entendre with it for extra credit.

In ‘Cymbeline’, the queen refers to Caesar’s ships bobbing around on the sea as ‘ignorant baubles’, describing them further as being like egg shells, being thrown and broken against the rocks.

A similar reference to boats as ‘baubles’ is made in ‘Troilus and Cressida.

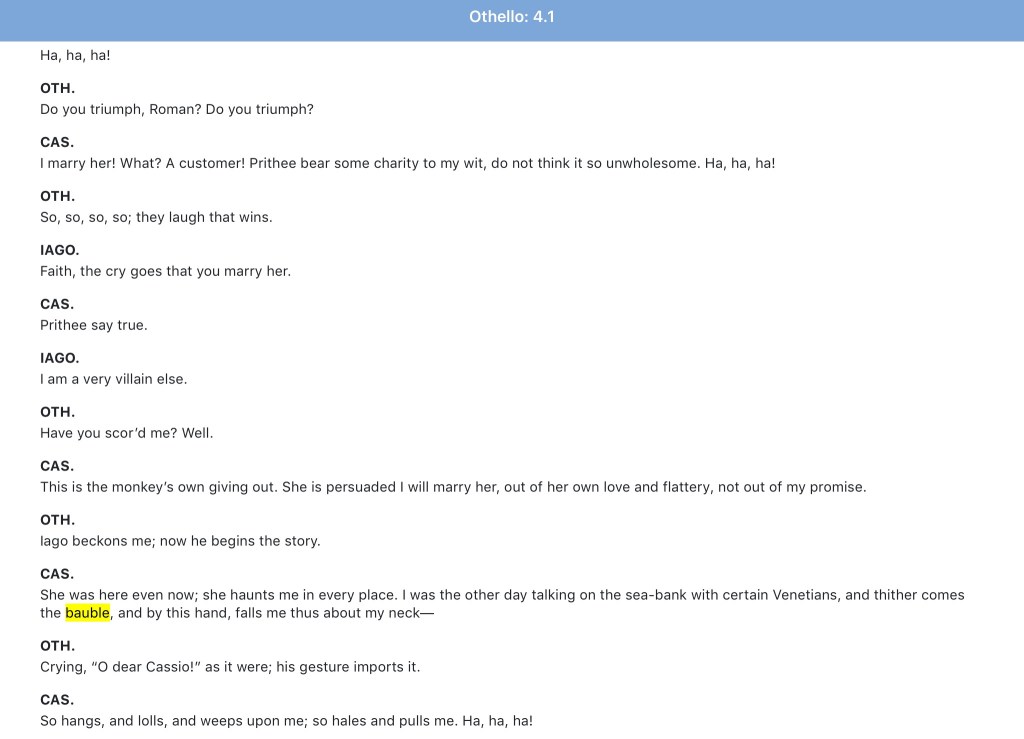

In ‘Othello’, Cassio shows his disregard for Bianca by describing her as a bauble that follows him around and tries to make him fall in love with her. That his companions laugh with him demonstrates that this use of the word to describe a pretty but not-so-valuable woman was easily understood at the time.

In ‘The Taming of the Shrew’, ‘bauble’ is used to refer to Kate’s hat – a decorative item of clothing, which is of little value in the play other than its use as a prop in her surprising demonstration of obedience to her husband, Petruchio.

‘Timon of Athens’ references a bauble as the staff of a jester or idiot, although in this instance, Aaron the Moor is suggesting that a king holding his sceptre and claiming to be faithful to God is the equivalent of his fool holding a bauble and pretending to be the king.

This sense of ‘bauble’ is extended in All’s Well That Ends Well, where the Clown refers to cheating on a man with his wife and giving her his bauble “to do her service”. Clearly, this is a pun on the jester’s staff, used to reference an altogether different kind of rod with a special ending on it.

This is Shakespeare’s trademark wit in action, taking common language and creating word play loaded with double entendre that would delight the masses and the ‘gentlemen’ alike.