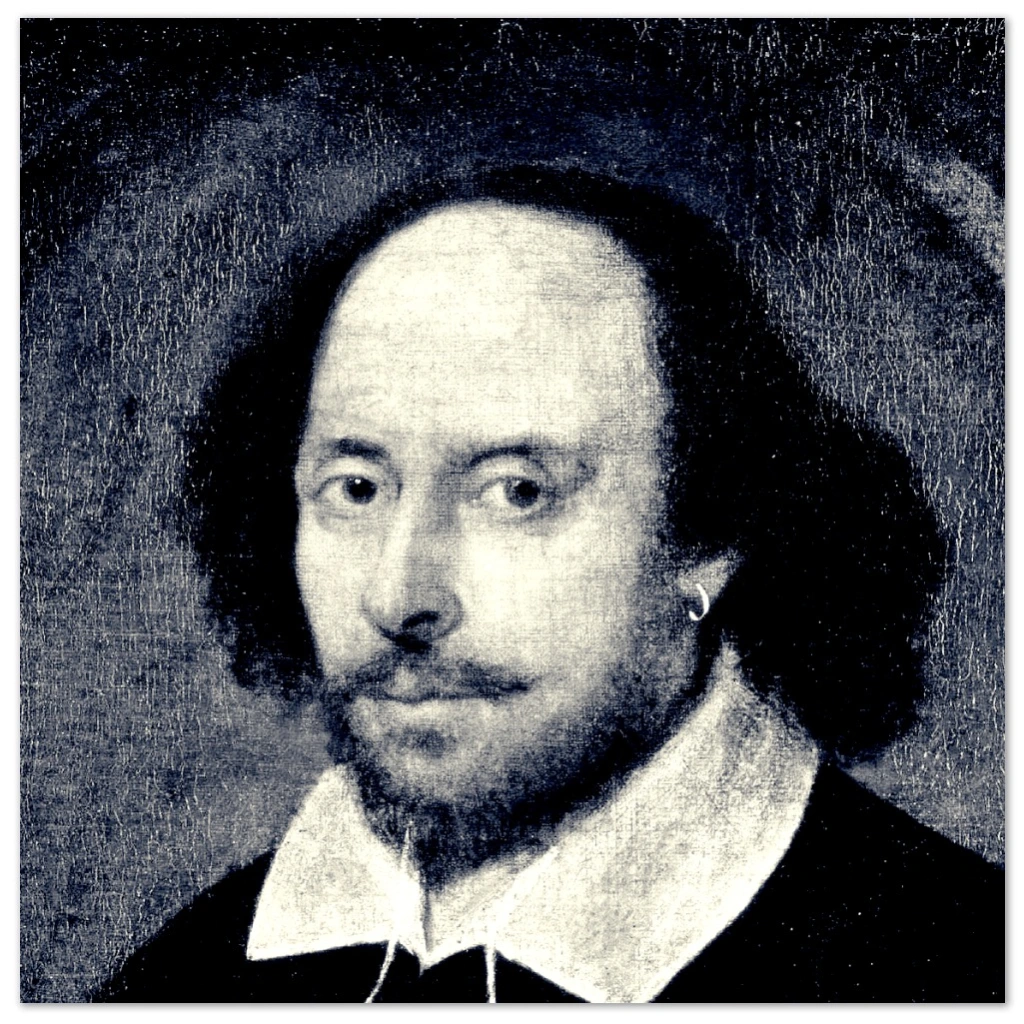

In my post about Sonnet 18, I commented that Shakespeare very evidently understood grief.

Nowhere in the canon of Shakespeare’s work is this more evident than in Hamlet.In this play, we see a son struggling with grief for his father and anger at the circumstances of his death. In this one young man’s experience, Shakespeare demonstrates some crucial lessons about grief.

Grief is natural.It is an instinctive immediate reaction to loss. Nobody questions why Hamlet mourns his father, except for those who conspicuously do not mourn the late king.

CLAUDIUS

How is it that the clouds still hang on you?

GERTRUDE

Good Hamlet, cast thy nighted color off,

And let thine eye look like a friend on Denmark.

Do not forever with thy vailed lids

Seek for thy noble father in the dust.

Thou know’st ’tis common, all that lives must die,

Passing through nature to eternity.

Hamlet, I.ii

It is those characters who do not feel or express grief who are portrayed as unnatural and heartless: had they been loyal, Gertrude, Claudius, and Polonius should all have been deeply affected by the death of the king and observed strict protocols of mourning as his wife, brother and trusted advisor. Instead, Gertrude marries Claudius, Claudius claims the throne that rightly should have gone to Hamlet, and Polonius switches his service seamlessly to the new regime. It’s all very convenient and it’s all very cold— but that’s how it goes when one is only in it for oneself.

This scene also demonstrates that grief is enduring. Unlike his mother, Hamlet doesn’t just “get over it”. That is not how most of us are designed. While it may change over time, grief is something that never fully goes away. It doesn’t take much to trigger a memory that unleashes a fresh wave of emotion.

HAMLET

O God, a beast that wants discourse of reason

Would have mourn’d longer—married with my uncle,

My father’s brother, but no more like my father

Than I to Hercules. Within a month,

Ere yet the salt of most unrighteous tears

Had left the flushing in her galled eyes,

She married—O most wicked speed: to post

With such dexterity to incestuous sheets,

It is not, nor it cannot come to good,

But break my heart, for I must hold my tongue.

Hamlet I.ii

Grief is existential. Grief makes us question the meaning of life: what’s the point of it all? Why are we here? What am I doing with my life? Is it worth going on? These are natural questions that many of us ask in response to the end of life, although perhaps less eloquently than Hamlet did.

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing, end them. To die, to sleep—

No more, and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to; ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wish’d. To die, to sleep—

To sleep, perchance to dream—ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come,

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause; there’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life:

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely,

The pangs of despis’d love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin; who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn

No traveler returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have,

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

Hamlet, III.ii

We often make observations like “life will never be the same” and that is essentially true. Grief often causes us to consider what is important and sort our priorities for life Thinking about the changes that someone’s death makes in our life can cause us to consider what we will do with the time, freedoms and opportunities that still lie ahead of us. This can be a time of significant decision making and resolution in response to the unavoidable change in our lives as a result of the death of a loved one.

Grief is pervasive. It affects every part of life, directly influencing motivations and willingness to meet commitments that all of a sudden seem mundane or irrelevant. It can take the joy out of other aspects of life that would otherwise bring joy, such as one’s relationships, achievements and career. Otherwise important things tend to be put on hold while grief holds the floor.

HAMLET

I have of late—but wherefore I know not—lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises; and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition, that this goodly frame, the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why, it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapors. What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving, how express and admirable in action, how like an angel in apprehension, how like a god! The beauty of the world; the paragon of animals; and yet to me what is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me—nor women neither, though by your smiling you seem to say so.

Hamlet III.i

It also has flow-on effects in the lives and experiences of others: when our emotions are most fragile, our relationships with others are proportionally vulnerable simply because of the impact of grief on one’s ability to connect and communicate effectively. The tendency to focus on one’s own self and situation may be a survival instinct in one sense, but it can also have a significant ripple effect among those around us.

Grief is relatable.The fact that we can all understand Hamlet’s feelings and responses show us that it is an integral element of life. Nobody lives forever, no matter how hard they try. That every society and culture has rituals and observances of death and mourning shows that grief is a universal experience: one which we will all encounter at some point in our lives.

From Hamlet, it is evident that there are constructive and destructive ways to deal with grief.

The pursuit of truth and justice, when necessary, is both healthy and appropriate. Questioning our priorities and examining our relationships can be a process of growth and refinement.

About, my brains! Hum—I have heard

That guilty creatures sitting at a play

Have by the very cunning of the scene

Been struck so to the soul, that presently

They have proclaim’d their malefactions:

For murder, though it have no tongue, will speak

With most miraculous organ. I’ll have these players

Play something like the murder of my father

Before mine uncle. I’ll observe his looks,

I’ll tent him to the quick. If ’a do blench,

I know my course. The spirit that I have seen

May be a dev’l, and the dev’l hath power

T’ assume a pleasing shape, yea, and perhaps,

Out of my weakness and my melancholy,

As he is very potent with such spirits,

Abuses me to damn me. I’ll have grounds

More relative than this—the play’s the thing

Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.

Hamlet, II.i

The observance and expression of grief is natural and should never be suppressed. The idea that men should not cry is not only unhealthy, it is absolute bunkum.

Grief complicates ones own emotions, affects mental and emotional health, adds pressure to relationships, and restricts one’s ability to ask for help.

It is crucial, then, to take great care to prevent grief leading us into self-destructive thoughts and behaviours.

HAMLET

O that this too too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew!

Or that the Everlasting had not fix’d

His canon ’gainst self-slaughter!

O God, God,How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world!

Fie on’t, ah fie!

Hamlet, I.ii

Thoughts of self-harm and suicide are a definite sign that someone is not coping with their emotions and their circumstances, and that they need trustworthy help and support.

Sacrificing our relationships with the living in the indulgence of grief for the dead. Hamlet’s rejection of Ophelia clearly had devastating consequences for her life, and ultimately caused more grief for those who knew and loved her.

HAMLET

I have heard of your paintings, well enough. God hath given you one face, and you make yourselves another. You jig and amble, and you lisp, you nickname God’s creatures and make your wantonness your ignorance. Go to, I’ll no more on’t, it hath made me mad. I say we will have no more marriage. Those that are married already (all but one) shall live, the rest shall keep as they are. To a nunn’ry, go.

Exit.

OPHELIA

O, what a noble mind is here o’erthrown!

The courtier’s, soldier’s, scholar’s, eye, tongue, sword,

Th’ expectation and rose of the fair state,

The glass of fashion and the mould of form,

Th’ observ’d of all observers, quite, quite down!

And I, of ladies most deject and wretched,

That suck’d the honey of his music vows,

Now see that noble and most sovereign reason

Like sweet bells jangled out of time, and harsh;

That unmatch’d form and stature of blown youth

Blasted with ecstasy. O, woe is me

T’ have seen what I have seen, see what I see!

Ophelia withdraws.

Hamlet III.i

Had Hamlet and Ophelia shared their thoughts and feelings with each other and others instead of internalising everything and shutting them out, things may have ended far more positively for them both.

Shakespeare demonstrates that grief is life-changing and long term. It is complex and challenging. Through the examples and experiences of the characters in Hamlet, we can consider and evaluate healthy and not-so-healthy ways of dealing with it. While everyone’s circumstances are different, we can each grow in empathy and understanding of the effects of grief on ourselves and other people.