My thanks to Mumble Theatre for this excellent post, which I found to be thoughtful, logical and very clearly explained.

I’d love to know what you think!

My thanks to Mumble Theatre for this excellent post, which I found to be thoughtful, logical and very clearly explained.

I’d love to know what you think!

While Shakespeare isn’t renowned for writing horror, he certainly understood the power of a macabre scene and the dramatic impact of horror when portraying just how evil a character could be.

He created a number of beautifully creepy and macabre scenes that hold definite appeal for horror fans, and which make great reading for October and Halloween.

The Problem of Female Agency in Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’

Tweet

#women #Shakespeare #ShakespeareSunday

The horror of Act 5, Scene 1 of Macbeth is subtle, but very real. While there is no real blood on the stage, there is definitely blood on Lady Macbeth’s hands.

After belittling Macbeth more than once for being haunted by visions and ghosts, the same thing happens to Lady Macbeth – or Lady Macdeath, as I like to call her. She is spared such public humiliation, though – her suffering is is revealed in the privacy of her own rooms, witnessed only by her servant and a doctor. This enables the audience to witness the intensely personal and intimate nature of the psychological horror experienced by Lady Macbeth.

In the chaos of her behaviour, the audience sees the extent of Lady Macbeth’s mental torment: she is plagued by guilt and losing her grip on reality. She walks and talks in her sleep, carrying a candle because she cannot bear to be in darkness, and speaking of fragments of bloody images and events. She repeatedly acts as though she is washing her hands, sometimes for fifteen minutes, yet she can never seem to get them clean. She keeps on finding blood on her hands: “Yet here’s a spot.”

Despair and frustration underscore pronouncements such as “Out, damned spot! Out, I say!” and “What! will these hands ne’er be clean?

In her mind, she can still clearly smell and see the blood on her own hands after the murder of Duncan, observing “Here’s the smell of the blood still: all the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand. Oh! oh! oh!”.

The doctor and gentlewoman who look on within the scene are disturbed by what they see before them, positioning the audience to share in their disquiet. Her macabre imagery and references to blood and ghosts cause the doctor to conclude that “Unnatural deeds

Do breed unnatural troubles; infected minds

To their deaf pillows will discharge their secrets;

More needs she the divine than the physician.”

The doctor speaks what the audience already knows: it is Lady Macbeth’s conscience rather than her hands that cannot be cleansed. When he instructs the gentlewoman to watch her carefully and remove anything that she might use to harm herself, he is alluding to things that Shakespeare’s generally superstitious audiences would have interpreted as horrific in itself – spiritual torment as a result of one’s own sins, and the thought of committing suicide in such a state, were appalling and dreadful to those who had been taught of the eternal damnation of one who took their own life or died otherwise completely unreconciled with God. The good folk of early modern England feared many things, but burial in unconsecrated ground and spending eternity in hell were right at the top of most people’s list of things they wanted to avoid. Had it been otherwise, the early modern church would have been far less powerful and prominent in the lives of the English people.

Throughout this scene, the power of a guilty conscience over one’s psyche is vividly expressed using the depiction and the imagery of horror.

Shakespeare also uses the Macbeths’ experiences as a distinct reminder of the fact that regicide is never a good idea because the consequences are enormous for the nation as a whole, but it also has significant and permanent spiritual consequences for the perpetrators. Given the number of plots against James I, a Scottish king long before he became an English one, this was a politically expedient message for Shakespeare to deliver to his audiences while at the same time telling a deliciously dark and macabre story.

The Problem of Female Agency in Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’

Tweet

#women #Shakespeare #ShakespeareSunday

You can read the whole scene, or the entire play, here.

While Shakespeare isn’t renowned for writing horror, he certainly understood the power of a macabre scene and the dramatic impact of horror when portraying just how evil a character could be.

He created a number of beautifully creepy and macabre scenes that hold definite appeal for horror fans, and which make great reading for October and Halloween.

‘Hamlet’ opens with a spooky, although not macabre, scene. This scene is all about those common elements that make horror work: creepy chills, fear and dread.

It’s the dead of night and the guards at Elsinore Castle are going about their regular duties, except that they seem nervous: Bernardo opens with the line “Who’s there?” and Marcellus leads their conversation leads with, “What, has this thing appeared again tonight?”

They are discussing the apparition that has appeared to them on the two previous nights. As they talk, the ghost appears again. It doesn’t speak to them, it doesn’t harm them… but it definitely scares them.

As they discuss the ghost and hypothesise as to whether or not it’s a bad omen, it returns, spreads its arms wide, and then disappears when a rooster crows.

Afterwards, Horatio tells Hamlet about seeing the ghost, and gives more detail of how frightened they were.

Like them, Hamlet thinks the appearance of the ghost is a sign that all is not right. His response is to keep watch with them that night, and when the ghost appears, he addresses it as his father’s ghost and entreats it to tell him what he needs to do.

Still fearful, Marcellus and Horatio tell Hamlet not to go with the ghost. He does, of course. How else would he find out what it wants to say to him?

It’s fair to say that Hamlet is more appalled by what the ghost of his father tells him than he is by seeing the ghost in the first place. The ghost says he was murdered by Claudius and urges Hamlet to take revenge, which is what drives the action of the remainder of the play.

The Problem of Female Agency in Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’

Tweet

#women #Shakespeare #ShakespeareSunday

This might not seem terrifying to audiences in the 21st century, but Shakespeare’s audiences were far more superstitious than we are, and they understood the significance of ghosts and omens. Just as the soldiers in the play “tremble and look pale”, most of the people in the early modern audience would likewise have taken that apparition very seriously.

This is delicious creepy horror that foreshadowed the Gothic style made popular by authors such as Walpole, Shelley, Stoker, Lovecraft, and even Charles Dickens, among others.

While Shakespeare isn’t renowned for writing horror, he certainly understood the power of a macabre scene and the dramatic impact of horror when portraying just how evil a character could be.

He created a number of beautifully creepy and macabre scenes that hold definite appeal for horror fans, and which make great reading for October and Halloween.

The Problem of Female Agency in Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’

Tweet

#women #Shakespeare #ShakespeareSunday

There is a beautifully crafted moment in Act 3, Scene 4 of ‘Macbeth’ where Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, and a group of lords gather for dinner. There is no place set for Banquo, because Macbeth knows he will not attend dinner – he cannot, because Macbeth has had him murdered.

Just as Macbeth is about to sit down, he makes a speech saying that all the greatest men of the kingdom would be under one roof if Banquo were there, but he hasn’t deigned to join them. At that moment, Banquo’s ghost has shown up and taken Macbeth’s seat. Macbeth, not realising the others can’t see Banquo, tells Ross he can’t sit down because the table’s full. Lennox shows him to his place, and Macbeth starts acting very strangely. He directly addresses Banquo’s ghost, saying “Thou canst not say I did it: never shake thy gory locks at me.”

This is a most macabre picture indeed. Banquo’s ghost isn’t all white and ethereal, it’s covered in blood and grey matter after having his head bashed in, to the point where his hair is dripping with it.

To the others at the table, the agitated and protesting Macbeth appears to be talking to no-one.

Ross assumes Macbeth is not feeling well. Lady Macbeth, as gracious and supportive of her husband as ever, tells them he’s having a brain snap, it happens all the time, and it will be over in no time if they ignore him. When she questions his masculinity, he says he is indeed a man – a bold enough one to look on something so scary that it would give the devil a fright. Then she tells him he’s imagining things again, and carrying on as though he were listening to an old woman’s fireside horror story.

He continues pointing it out – “Prithee, see there! behold! look! lo!” and tells the ghost that if it can nod, it should speak to him too. Macbeth knows exactly what – or who – he is seeing, and it terrifies him.

The scene is quite bizarre. The man who is ostensibly the king of Scotland starts talking to nobody and his wife undermines both his sanity and his manhood in front of all his lords. The dramatic irony of the audience knowing Banquo’s ghost has appeared, while the other attendees at the dinner do not, is compelling, giving the audience a powerful sense of horror — both at the scene as they witness it, and at the thought of what is to become of the kingdom. It contributes to the building sense of impending doom and adds another layer of darkness to this most bloody tragedy.

The Problem of Female Agency in Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’

Tweet

#women #Shakespeare #ShakespeareSunday

Read the rest of the scene – or the whole play – here.

Check out Mya Gosling’s brilliant cartoon version of this scene at Good Tickle Brain.

While Shakespeare isn’t renowned for writing horror, he certainly understood the power of a macabre scene and the dramatic impact of horror when portraying just how evil a character could be.

He created a number of beautifully creepy and macabre scenes that hold definite appeal for horror fans, and which make great reading for October and Halloween.

There is one particularly macabre scene in King Lear where Lear’s daughter Regan and her husband, Cornwall, presided over the punishment of Gloucester for his “treason” in supporting Lear, the rightful king, after their rejection of him.

They are in Gloucester’s own home, no less, when they detain him, bind him to a chair and accuse him of treason. He has no idea of their evil intent, and reminds them more than once that they are his guests – and terrible ones at that.

Regan yanks hair out of Gloucester’s beard, and when Cornwall gouges out one of his eyes, presumably with a dagger, she picks up a sword and kills the servant who objects, then demands that Gloucester’s other eye be taken out, too. On doing so, Cornwall utters the words, “Out, vile jelly!” This really emphasises the vulnerability and delicate nature of the tissues and substance of the eye, and adds a brutally heartless element to the already macabre action.

Once Gloucester’s eyes are both out, Regan and Cornwall send him away bleeding and blinded while Cornwall complains that he has been hurt and demands that Regan takes care of him because he has a boo-boo. The fact that Cornwall is both still alive and able to see where he’s going demonstrates that he is nowhere near as badly hurt as either Gloucester or the dead servant, the irony of which is not lost on the audience, and underscores the self-absorbed evil of the pair.

It’s a grisly, gory scene that would fit right into any horror story or film.

I have included the scene below.

You might also check out Mya Gosling’s excellent cartoon recreation of the scene at Good Tickle Brain.

The Problem of Female Agency in Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’

Tweet

#women #Shakespeare #ShakespeareSunday

ACT III, SCENE VII. Gloucester’s castle.

Enter CORNWALL, REGAN, GONERIL, EDMUND, and Servants

CORNWALL Post speedily to my lord your husband; show him this letter: the army of France is landed. Seek out the villain Gloucester.

Exeunt some of the Servants

REGAN Hang him instantly.

GONERIL Pluck out his eyes.

CORNWALL Leave him to my displeasure. Edmund, keep you our sister company: the revenges we are bound to take upon your traitorous father are not fit for your beholding. Advise the duke, where you are going, toa most festinate preparation: we are bound to the like. Our posts shall be swift and intelligent betwixt us. Farewell, dear sister: farewell, my lord of Gloucester.

Enter OSWALD

How now! where’s the king?

OSWALD My lord of Gloucester hath convey’d him hence:

Some five or six and thirty of his knights,

Hot questrists after him, met him at gate;

Who, with some other of the lords dependants,

Are gone with him towards Dover; where they boast

To have well-armed friends.

CORNWALL Get horses for your mistress.

GONERIL Farewell, sweet lord, and sister.

CORNWALL Edmund, farewell.

Exeunt GONERIL, EDMUND, and OSWALD

Go seek the traitor Gloucester,

Pinion him like a thief, bring him before us.

Exeunt other Servants

Though well we may not pass upon his life

Without the form of justice, yet our power

Shall do a courtesy to our wrath, which men

May blame, but not control. Who’s there? the traitor?

Enter GLOUCESTER, brought in by two or three

REGAN Ingrateful fox! ’tis he.

CORNWALL Bind fast his corky arms.

GLOUCESTER What mean your graces? Good my friends, consider

You are my guests: do me no foul play, friends.

CORNWALL Bind him, I say.

Servants bind him

REGAN Hard, hard. O filthy traitor!

GLOUCESTER Unmerciful lady as you are, I’m none.

CORNWALL To this chair bind him. Villain, thou shalt find–

REGAN plucks his beard

GLOUCESTER By the kind gods, ’tis most ignobly done

To pluck me by the beard.

REGAN So white, and such a traitor!

GLOUCESTER Naughty lady,

These hairs, which thou dost ravish from my chin,

Will quicken, and accuse thee: I am your host:

With robbers’ hands my hospitable favours

You should not ruffle thus. What will you do?

CORNWALL Come, sir, what letters had you late from France?

REGAN Be simple answerer, for we know the truth.

CORNWALL And what confederacy have you with the traitors

Late footed in the kingdom?

REGAN To whose hands have you sent the lunatic king? Speak.

GLOUCESTER I have a letter guessingly set down,

Which came from one that’s of a neutral heart,

And not from one opposed.

CORNWALL Cunning.

REGAN And false.

CORNWALL Where hast thou sent the king?

GLOUCESTER To Dover.

REGAN Wherefore to Dover? Wast thou not charged at peril—

CORNWALL Wherefore to Dover? Let him first answer that.

GLOUCESTER I am tied to the stake, and I must stand the course.

REGAN Wherefore to Dover, sir?

GLOUCESTER Because I would not see thy cruel nails

Pluck out his poor old eyes; nor thy fierce sister

In his anointed flesh stick boarish fangs.

The sea, with such a storm as his bare head

In hell-black night endured, would have buoy’d up,

And quench’d the stelled fires:

Yet, poor old heart, he holp the heavens to rain.

If wolves had at thy gate howl’d that stern time,

Thou shouldst have said ‘Good porter, turn the key,

‘All cruels else subscribed: but I shall see

The winged vengeance overtake such children.

CORNWALL See’t shalt thou never. Fellows, hold the chair.

Upon these eyes of thine I’ll set my foot.

GLOUCESTER He that will think to live till he be old,

Give me some help! O cruel! O you gods!

REGAN One side will mock another; the other too.

CORNWALL If you see vengeance,—

First Servant Hold your hand, my lord:

I have served you ever since I was a child;

But better service have I never done you

Than now to bid you hold.

REGANHow now, you dog!

First ServantIf you did wear a beard upon your chin,

I’d shake it on this quarrel. What do you mean?

CORNWALLMy villain!

They draw and fight

First ServantNay, then, come on, and take the chance of anger.

REGANGive me thy sword. A peasant stand up thus!

Takes a sword, and runs at him behind

First Servant O, I am slain! My lord, you have one eye left

To see some mischief on him. O!

Dies

CORNWALL Lest it see more, prevent it. Out, vile jelly!

Where is thy lustre now?

GLOUCESTER All dark and comfortless. Where’s my son Edmund?

Edmund, enkindle all the sparks of nature,

To quit this horrid act.

REGAN Out, treacherous villain!

Thou call’st on him that hates thee: it was he

That made the overture of thy treasons to us;

Who is too good to pity thee.

GLOUCESTER O my follies! then Edgar was abused.

Kind gods, forgive me that, and prosper him!

REGANGo thrust him out at gates, and let him smell

His way to Dover.

Exit one with GLOUCESTER How is’t, my lord? how look you?

CORNWALL I have received a hurt: follow me, lady.

Turn out that eyeless villain; throw this slave

Upon the dunghill. Regan, I bleed apace:

Untimely comes this hurt: give me your arm.

Exit CORNWALL, led by REGAN

Second ServantI’ll never care what wickedness I do,

If this man come to good.

Third Servant If she live long,

And in the end meet the old course of death,

Women will all turn monsters.

Second Servant Let’s follow the old earl, and get the Bedlam

To lead him where he would: his roguish madness

Allows itself to any thing.

Third Servant Go thou: I’ll fetch some flax and whites of eggs

To apply to his bleeding face. Now, heaven help him!

Exeunt severally

The Problem of Female Agency in Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of the Shrew’

Tweet

#women #Shakespeare #ShakespeareSunday

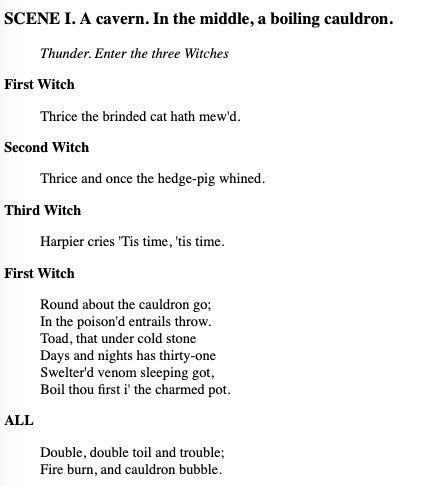

I have more than one friend who likes to stir a pot of whatever they are cooking and say in a witchy voice: “Bubble bubble, toil and trouble…”

At times – usually when it is someone I don’t know well – I choose to be diplomatic and just let them go. They’re having fun.

When it’s a friend who I know will not be offended, I have told them gently what the correct line is, and given them a few extra lines to use when the family asks, “What’s for dinner?” “Eye of newt and toe of frog” is a family favourite in my own kitchen, with “fillet of a fenny snake” a close second.

When I asked one of them if she knew she was quoting Ducktales, not Shakespeare, she took it in her stride and immediately switched to a voice that sounded almost exactly like Donald Duck. It was most impressive, and I should have been less surprised by that given that we’ve done theatre together.

Still, it is a quote that people do get wrong.

In the opening scene of Macbeth, he witches actually say “Double, double, toil and trouble, / Fire burn and cauldron bubble” as the refrain of their song about making a potion in the cauldron in the centre of the stage.

My favourite opening scene among all Shakespeare’s plays, this is a passage that is super cool and super creepy at the same time. Despite the fact that the witches are brewing something potent, the song concludes with a witch declaring that “something wicked comes” when Macbeth enters. It’s a powerful statement of how dark and deadly the central character of the play will turn out to be.

Pretty much anywhere you go, whoever you talk to, if they know only one thing about any play by Shakespeare, it’s the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet. It’s possibly the most famous scene ever written.

There’s just one problem with that: there was no balcony.

That’s correct.

There.

Never.

Was.

A.

Freaking.

Balcony.

In the script, the stage direction is clear: JULIET appears above at a window.

Not a balcony. A window.

You can read the entire scene and see that not once is a balcony mentioned.

I don’t know who invented it, but it was a killer idea that I bet Shakespeare would wish he had thought of, were he still alive today.

Of course, directors can stage a play however they like, and make use of whatever structures, sets and furniture is available to them.

Filmmakers can do likewise, but one must keep in mind their tendency to just change whatever they want. Hollywood is notorious for that. The mayhem that comes from mass misunderstanding occurs when directors think they know better than the author, and when people watch a movie instead of reading the book.

It makes people and their assumptions about the original text wrong, and leaves them marinating in their wrongness until their wrongness is so commonly accepted that most people think it’s right.

It just goes to show that what your English teacher always said is true: there really is no substitute for reading the book.

These days, when people talk about a “foregone conclusion” they mean something is a given: it is inevitable, it will happen, it may safely be assumed. As certain as it sounds, it is still a statement of conjecture about an event that is yet to occur.

When Shakespeare had Othello speak those words in Act 3, Scene 3 of the play that bears his name, it had quite the opposite meaning.

In this scene, Iago is manipulating Othello’s thoughts and making him believe that Desdemona has cheated on him.

Othello says, “But this denotes a foregone conclusion: Tis a shrewd doubt, though it be a dream.”

Here, he is speaking of the adultery between Desdemona and Cassio as something that he is certain has already happened. This gives the phrase “foregone conclusion” the opposite meaning to that which it holds today.

This, and statements such as “I’ll tear her all to pieces” and “O blood, blood, blood!” are evidence that Othello has already made up his mind about the guilt of his wife and former second-in-command.

The scene ends with Othello swearing his loyalty to Iago and thinking of ways to kill Desdemona. Charming, I know.

This morning’s conversation in my kitchen is a clear demonstration of just how much of a Shakespeare Nerd I really am.

H: I need egg cartons. Where do I get egg cartons?

Me: How many do you want?

I pointed to the top of my fridge where there sat a stack of egg cartons.

Me again: Take them all.

H: Oh wow! Thanks!

K: That’s awesome! I’ll grab them in one foul swoop and put them in the car.

Me: Well, that’s decided my blog post for today.

K: Huh?

In Act 4, Scene 3 of ‘Macbeth’, Malcolm and Macduff engage in testing one another’s loyalty to Scotland rather than to Macbeth, who has become king. During that conversation, Macduff learns of the murders of his wife and children at the order of Macbeth, whom he describes as a “hell-kite” who has slain his “chickens” in “one fell swoop”.

The deed was certainly foul, but that isn’t what Shakespeare wrote. He wrote “one fell swoop” which is an entirely different thing.

Here, fell means ‘fierce’.

It’s an image of violent attack, of hunting, and of predator and prey, which leaves the audience in no doubt that these murders were calculated and precise. The term “hell-kite” leaves the audience in no doubt of the evil motivations behind the slaying.

These days we understand the phrase “sea change” to reflect something new and positive in one’s life. It is frequently used to describe a significant transformation in a person or in one’s lifestyle.

In Australia, it has also come to mean a physical move from the city or the country to live closer to the ocean, or even taking a holiday at the beach.

The phrase hasn’t always had such positive associations.

In Act 1, Scene 2 of Shakespeare’s play ’The Tempest’, Prospero’s familiar spirit Ariel sings a song that makes Ferdinand believe that his father, Alonso, has drowned in a shipwreck, and that his father is buried at sea “full fathom five”, or five fathoms deep. Through the action of the water on his remains, his body is undergoing substantive changes: his eyes are turning into pearls and his bones into coral. There is nothing left of him that has not been transformed by the sea.

Even worse, this story of the shipwreck and drowning is not true. It is, in fact, a ruse by Prospero to orchestrate a marriage match between his daughter, Miranda, and Ferdinand. Prospero is quite comfortable with using trickery and misleading magic to achieve what he wants to, and this is not the only time during this play that he willingly deceives others to get what he wants.

So, even though it does still reflect a significant transformation, it has much darker connotations than the term does now. Deceit, manipulation, grief and emotional blackmail all factor into the origins of this phrase that we use so differently today.