Knowing the literary devices used by Shakespeare and how they work helps those who read or study his works understand the ways in which he has shaped and crafted meaning in the lines delivered by his characters and in his poetry. It also helps readers to recognise the difference between literal and figurative language, and therefore to interpret more correctly the message of particular lines and scenes, and of texts as a whole.

Of course, there are the standard ones that everyone should learn in school: simile, metaphor, alliteration, repetition hyperbole. In senior high, that should extend to more sophisticated devices specific to the text being studied. My senior English class is studying ‘RichardIII’, so they are learning about stichomythia, anaphora and antithesis among others. Irony and dramatic irony are also heavy hitters in this play, so while they are by no means new concepts to the students, we are discussing them in detail.

An excellent online resource for the definition and demonstration of rhetorical devices used by Shakespeare and many other dramatists, orators and writers is Silva Rhetoricæ.

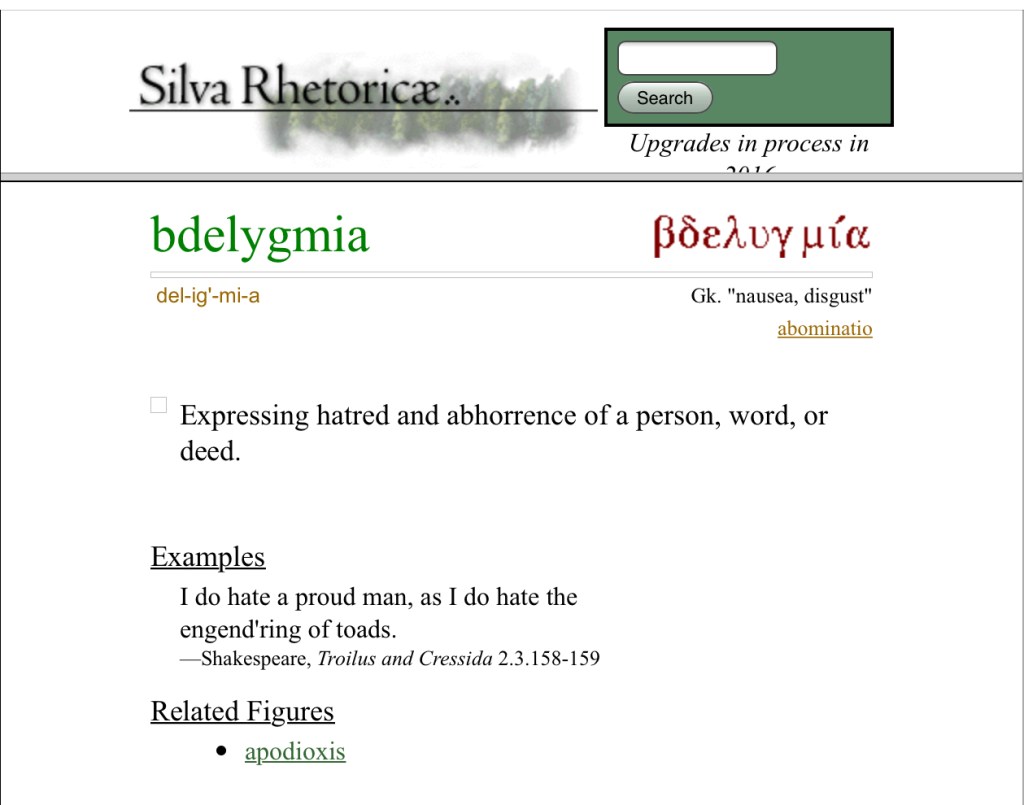

The site is knowledgeable and fairly thorough, although some terms relating to Shakespeare’s plays are not included. The names of rhetorical devices are listed alphabetically, and the definitions are written in plain English with examples and alternative terms provided. There is also a handy pronunciation guide, which is really helpful when it comes to terms like ‘bdelygmia’ and ‘symploce’.

While I do not expect my students to use the same degree of metalanguage that university students might use, there is definitely credit in nailing the key terms and using them to write about a text with greater eloquence and sophistication.